The intersection of black history and beer is a narrow one. Most folks, I believe, would be hard pressed to name two African-Americans who have made a mark on the chalkboard of beer history.

I say two because Garrett Oliver has become a household name among beer aficionados. He started as an apprentice at Brooklyn Brewery, rose to head brewer in 1994 and has written and edited numerous books, including two of my go-to resources, The Brewmaster’s Table and The Oxford Companion to Beer.

Beyond Oliver, few African-American names jump to the tip of the tongue of Joe Blow beer lover. That’s a shame, because the history of black involvement in American brewing is a rich one, reaching back to colonial times and rubbing shoulders with the nation’s founders. Black History Month affords an opportunity to tell that story, and I’d been struggling to find a springboard to launch into the subject until yesterday, when a friend shared a piece published in USA Today. The headline reads: “Craft brewers seek to involve more African Americans.” The article quotes Oliver and several others in the industry, such as Kevin Blodger of Union Craft Brewing in Baltimore and Mark and Sharon Ridley, owners of a Brass Tap franchise in the D.C. metro area of Maryland.

It would have been unreasonable to expect the article to go back centuries to include names such as Peter Hemings. Or Bagwell Granger. Or Daniel Farley. Or the Nottoway Negroes. Or a ditcher named Botswain who sold George Washington six pounds of hops in 1798.

All of these Virginians were slaves except for Farley. He was a free black man living in Charlottesville who probably made his own homebrew and definitely sold hops to Thomas Jefferson for brewing at Monticello. And there we come to the most luminous intersection of black history and beer, in the figure of Peter Hemings. I contend that Hemings was the first black person professionally trained in the brewing arts in this country. His story exists within a broader context, though, which deserves wider appreciation for the role of slaves in making beer. The past can inspire the present, and it’s my hope that stories of Virginia’s black brewing history can frame a proud legacy and a sense of identity for African American beer lovers.

First, a bit of background. Beer has been with us since the dawn of civilization, perhaps even before hunter-gathers settled into an agrarian lifestyle. Beer was brewed by Native Americans before Europeans arrived. Beer was on board the three ships that delivered English settlers to Jamestown in 1607. And beer was a staple on plantations as those settlers moved westward into the Virginia wilderness.

The chore of producing sufficient ale to fortify family members and guests in this part of the country fell to the plantation mistress. Her role was largely supervisory—securing recipes, procuring ingredients, scheduling batches, ensuring quality—while the actual hands-on brewing in the kitchen was conducted by slaves. Brewing was a skill much valued, as shown in this ad in a Virginia newspaper: For sale: A valuable young Negro woman, very well qualified for all sorts of Housework, as Washing, Ironing, Sewing, Brewing, Baking, &c.

To brew good beer, you need the right ingredients. Although everything from persimmons to pea pods was used in colonial brew pots, traditional elements such as hops and barley provided the best ale. Virginia’s climate frowned on efforts to cultivate barley, but hops, which are a native species (according to Thomas Jefferson), grew readily, both wild on river banks and on homesteads. Landon Carter, son of Robert “King” Carter and one of the colonial era’s most prominent plantation owners, wrote a 16-page essay in the mid-1700s on growing hops. He described how to choose the best site, prepare the soil, train the bines to grow properly, harvest the cones and dry them for brewing. Being a wealthy planter with many civic and military duties in addition to running the Sabine Hall estate, Carter probably spent little time digging holes, shoveling manure or picking the sticky, rough hops. Those chores fell to slaves.

And at least some of those slaves paid attention and learned, as numerous records indicate. In addition to Botswain’s transaction with George Washington, bookkeepers at the College of William and Mary (where evidence indicates that a brew house existed in the 1700s) noted purchases of hops from a group named simply the “Nottoway Negroes.”

The most telling tale comes from Monticello. Martha Jefferson, Thomas’ wife, was a prolific brewer. Her household accounts mention sixteen batches brewed her first year there, 1772-73, and from all indications those ales were well-hopped. She bought some hops from slaves at neighboring estates, but the gardens of slaves at Monticello served as a source for many of those hops. Though the Jeffersons purchased all kinds of produce, fish, game and other consumables from their slaves, “Hops was among the most frequently purchased product from the slave community by Martha,” writes author Peter Hatch, former director of gardens and grounds at Monticello.

On Oct. 24, 1774, Martha noted: “Bought 7 lb of hops with an old shirt.” At the other end of the spectrum, in 1818 (well after Martha’s death in 1782), Thomas Jefferson paid Bagwell Granger, a notable figure in Monticello’s slave community, the amount of $20 for sixty pounds of hops. That equals about $800 today. “That seems like a lot,” noted one historian/author I consulted. “Still, it’s a fraction of what it would have cost to buy a family member’s freedom, when you think of it in that context.”

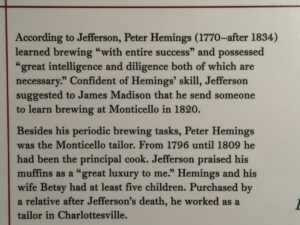

By the time of that purchase, brewing at Monticello was progressing on a sizable scale, thanks to Peter Hemings. A brother to Sally, James and others of the Hemings family, Peter served primarily as a tailor and chef. In 1813, however, Thomas Jefferson invited Capt. Joseph Miller to stay at Monticello and train Hemings as a brewer. Miller had been a professional brewer in London before coming to America to claim family estates and “to establish a brewery in which art I think him as skillful a man as has ever come to America,” Jefferson wrote.

Peter Hemings apparently was a quick study in brewing as well as his other skills and absorbed sophisticated brewing techniques. Jefferson described him as possessing “great intelligence and diligence both of which are necessary.” Improvisation also was required because barley, beer’s grain of choice, was not grown at the plantation and was expensive to import. So in 1814, they began to malt wheat; corn followed after Miller’s departure.

So, what was the beer like? Jefferson kept no recipes, but he did not tolerate insipid beer. He specified a bushel of malt for every eight to ten gallons of “strong beer, such as will keep for years.” And three-quarters of a pound of hops was used for every bushel of wheat.

Monticello’s brewing schedule was seasonal. In the fall, three sixty-gallon casks of ale were brewed in succession. Similar brewing followed in the spring. For production on that scale, Monticello needed a brew house, built in time for brewing in the fall of 1814. An undated drawing shows Jefferson’s plans for a Palladian-style brew house, but it is unknown if it was ever built. The location of the brew house that was used has not been determined, but Hemings would have been the hands-on supervisor of the ales it produced. Hemings was so accomplished that Jefferson invited his friend James Madison to send someone to learn from Peter.

Little else is known of Hemings other than a touching episode after Jefferson’s death in 1826. A lifetime of debt saddled the estate, and Jefferson’s heirs decided to hold an auction of property, including slaves in January 1827. The aforementioned Daniel Farley was one of those at the auction. Records suggest that Farley was the oldest son of Mary Hemings. That would have made him Peter Hemings’ nephew, though Farley was only two years younger than Monticello’s brewer, who was 57. Despite his age, Peter Hemings was appraised at the auction for $100, probably due to his multiple skills. Farley was able to purchase him for $1. “The token sale price suggests that the wish of his family members to purchase his freedom was recognized by those present at the sale,” noted one historian.

Peter Hemings lived out his days as a tailor in Charlottesville. No records indicate that he continued brewing. His legacy of making beer at Monticello, however, survives. Visitors to the “little mountain” will find a display of his brewing tools in a special exhibit. It falls to us to spread the word of his accomplishments and honor his name.

Pingback: Book Review: Mallory O’Meara’s Girly Drinks – Oregon Beer History

Thanks for including the link to my site. Much appreciated.