It’s easy to imagine the pitch that must have been on the table in the boardroom of Milwaukee’s Blatz Brewing Company in 1951.

“Look, boss, the world’s most popular radio program is going to this new format—yes, television. They’re switching from these two white guys doing blackface-type comedy to using real Negro actors. We’ve been supporting Negro rights for years, and this is an opportunity to provide corporate backing and reach a whole new audience. Whatta ya say, boss?”

The answer was a no-brainer “yes.” But the decision would put Blatz in the eye of a storm of racial tensions, many of which still swirl in America.

In the early 1930s, the brewing industry found itself playing catch-up in employing Negro workers. Prohibition’s repeal in 1933 promised better times, yet the quicksand of the Great Depression swallowed much of that optimism. The federal government’s New Deal initiatives were met with skepticism in some quarters.

“The ‘new deal’ as a campaign slogan last fall elicited much favorable comment and attention from the masses of people,” reads an opinion piece in the June 10, 1933, edition of the Detroit Tribune (the self-described “Leading Negro Weekly of Michigan”). “Stroh’s brewery, a home concern, it is said does not hire a single Negro in its brewery system. Yet, according to their advertisement, they are conscientious new deal enthusiasts. I wonder if they realize just what the new deal means to a Negro?” The editorial singles out Schlitz for making “good beer” and hiring “Negroes in all capacities,” but the writer questions why Negroes should support restaurants, cabarets and other beer-selling businesses “which in turn do nothing to reciprocate their patronage.”

Big brewers began making small changes, particularly in hiring Negro salesmen. By 1935, Pfeiffer in Detroit had a dozen black employees in sales and office positions; Eckhardt & Becker Brewing Company, also of Detroit, boasted a handful in similar jobs. Anheuser-Busch was petitioned, however, to remedy shortcomings after representatives of the Chicago NAACP toured its St. Louis plant that year. “Not one American Negro was seen working in the entire plant [but] two colored men are employed as personal servants in the Busch family,” says a July 27, 1935, article in Detroit’s Tribune Independent (its banner reads “On Guard for Negro Rights”).

While these slight inroads were being made in sales and office jobs, little progress was seen among production workers. The Detroit chapter of the American Federation of Labor faced accusations in 1935 that Negroes were being kept out of the Detroit Brewery Workers Union “because of prejudice.” The union countered that it was not accepting new members, white or black, because so many existing members were still unemployed in the wake of Prohibition, according to the Tribune Independent.

Boycotts surfaced. A 1938 effort targeting Stroh Brewing Company alleged racial discrimination; an investigation revealed the brewery had two Negro employees when the boycott was launched a year earlier, and two more were hired after. Charges were dropped after the executive committee of the Paradise Valley Consumers League in Detroit had an “audience” with John Stroh, grandson of the company’s founder.

“We found the circumstances and policies of said brewery…were entirely different, when once we were in the presence of the official family,” reads the report from the League’s executive committee. “The parties accused knew not of any reason why they could be justly accused of unfairness by any group or groups, of displaying any attempted prejudices at any time. They stated that they are willing at any time to concede to our group an open-door policy.”

Oddly, the boycott of Stroh continued, as did protests elsewhere. In Texas, a Black nightclub owner named Julius White assembled fellow Houston businessmen in early 1939 and formed the Houston Colored Beer Dealers Association to protest the absence of Black employees in the state’s brewing industry. They claimed that despite Negroes consuming more than 50 percent of the beer sold in the city, “none of the Texas breweries and the out-of-state ones selling beer here had Negroes in sales positions.” They threatened a boycott unless “a Negro salesman called at the establishments to handle the sale of the product.” The breweries capitulated. “Today, every firm selling beer in Houston has one or two colored sales representatives,” reads an Associated Negro Press article in August 1939.

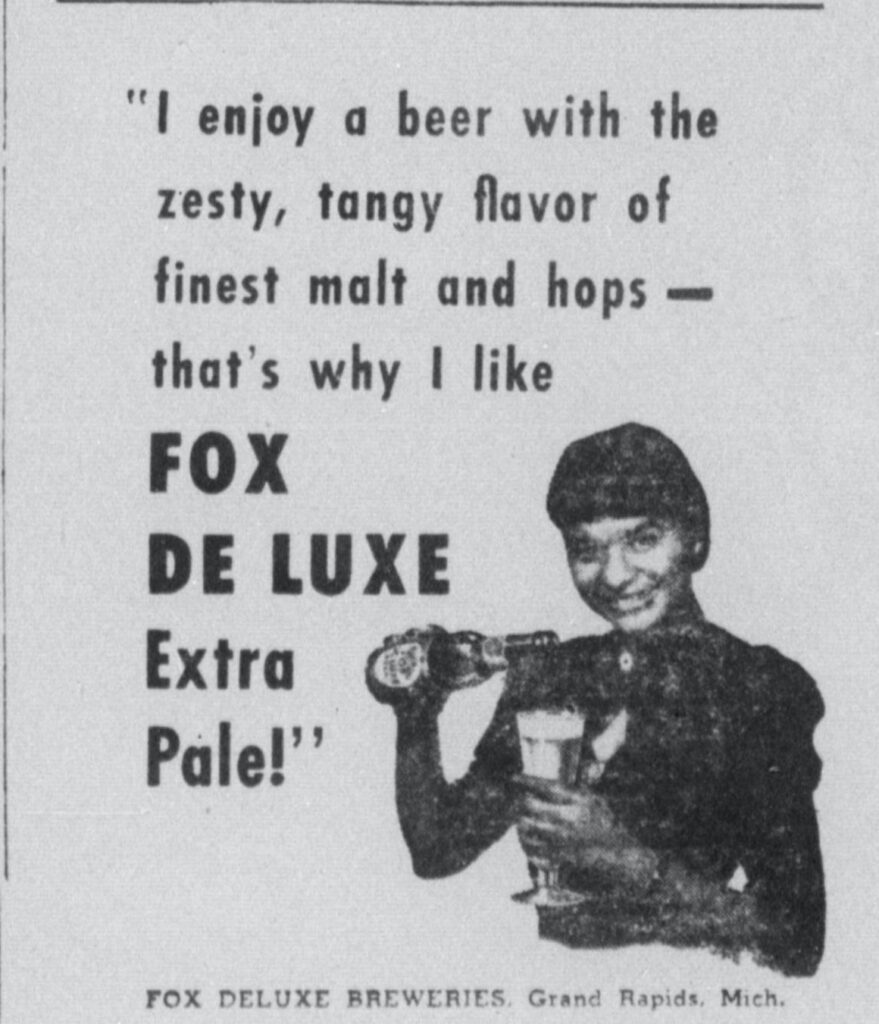

Black women as well as men were used in ads promoting Fox De Luxe beers from Grand Rapids, Mich. Taken from the Detroit Tribune of Saturday, June 21, 1947.

The Negro presence in the brewing industry continued to grow. Back in Detroit’s Paradise Valley—a Black community where entrepreneurship flourished—the Paradise Valley Distributing Company (“the world’s only Colored beer distributorship,” it claimed) stood as a beacon to Black enterprise. Fox De Luxe ads in the late 1930s and 1940s showed Black men in suits and ties (and the occasional well-dressed woman) hoisting pilsner glasses of beer.

On the other side of the coin, a 1947 Budweiser ad showed a Negro porter grinning obsequiously while serving two besuited white men in a railroad dining car.

It wasn’t until 1950 that a true breakthrough occurred. “Breweries Lift Ban,” shouts a front-page headline in the July 29, 1950, issue of the Detroit Tribune. “A half-century-old pattern of employment practices in the brewery industry of the United States has at last been modernized, according to the National Urban League Department of Industrial Relations. With employment of some 25 Negroes in production phases by three major firms in Milwaukee, the capital city of brewing industry, exclusion of Negro workers has at last been superseded. This, said the League, signals the opening of a new and important occupational field for Negro labor.”

It wasn’t until 1950 that a true breakthrough occurred. “Breweries Lift Ban,” shouts a front-page headline in the July 29, 1950, issue of the Detroit Tribune. “A half-century-old pattern of employment practices in the brewery industry of the United States has at last been modernized, according to the National Urban League Department of Industrial Relations. With employment of some 25 Negroes in production phases by three major firms in Milwaukee, the capital city of brewing industry, exclusion of Negro workers has at last been superseded. This, said the League, signals the opening of a new and important occupational field for Negro labor.”

The Blatz, Pabst and Schlitz brewing companies had worked with the CIO Brewery and Distillery Workers Milwaukee local to achieve the step after years of negotiating. Blatz, which was owned by Schenley Industries, stated, “For many years our organization has employed Negroes on its sales staff, and now, with the addition of personnel we are confident that they, too, will be a strong and useful addition to our company.”

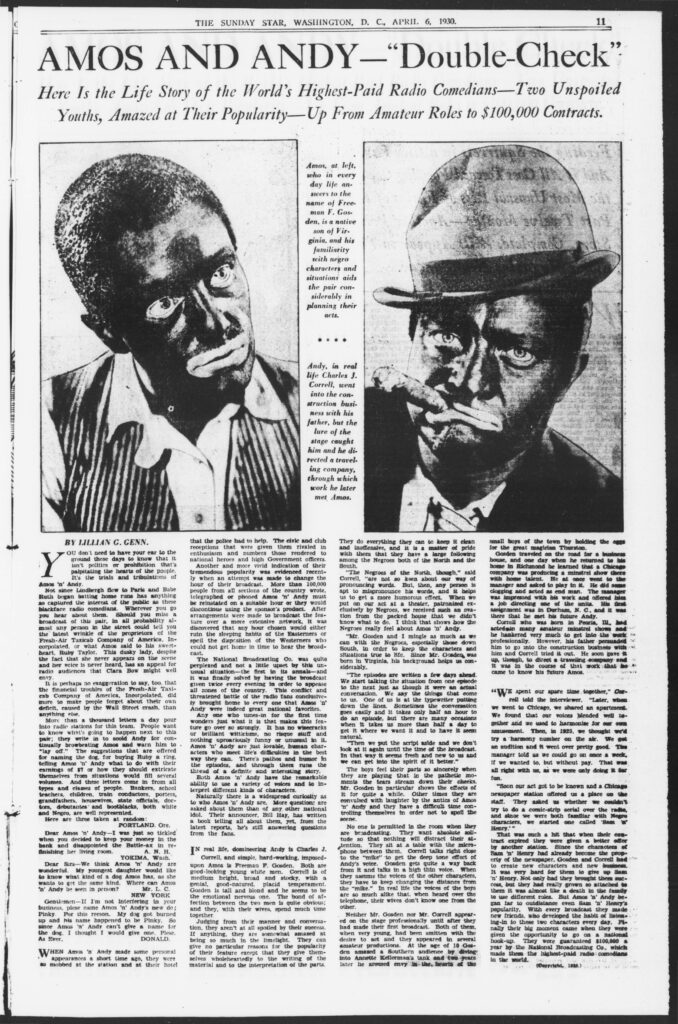

This integration of the brewing industry was occurring while a starkly different representation of Black life was holding the country in thrall. “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” a radio program started in 1928 and featuring two white men doing blackface-type comedy, built a following that bordered on mania. The stars were invited to the White House, their appearances in public drew thousands of fans, their names were emblazoned in stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and by 1930 they were the world’s highest-paid radio comedians.

“Not since Lindbergh flew to Paris and Babe Ruth began batting home runs has anything so captured the interest of the public as these blackface radio comedians. Wherever you go, you hear about them,” Lillian G. Genn wrote in an April 6, 1930, full-page feature in the Washington Evening Star.

Amos, described by Genn as “simple, hard-working [and] imposed-upon,” was portrayed by Freeman F. Gosden. He grew up in Richmond, Va., former capital of the Confederacy, and his father, W.W. Gosden, rode with the 43rdBattalion of the Virginia Cavalry, led by John Singleton Mosby (aka “the Gray Ghost”). Freeman Gosden had a hankering to be an actor, and when a Chicago company came to Richmond to produce a minstrel show, he landed a job. “His first assignment was Durham, N.C., and it was there he met his future Andy.”

Charles J. Correll, a native of Peoria, Ill., also had some experience in minstrel shows. The two hit it off and ended up in Chicago, where they developed a show called “Sam ‘n’ Henry,” a short-lived precursor to “Amos ‘n’ Andy.” Gosden and Correll wrote the scripts, portraying two Negroes living and doing business in Harlem, N.Y. The characters were caricatures—speaking in dialect, mispronouncing words, getting into all kinds of mishaps and mischief as they operated the Fresh-Air Taxicab Company of America, Incorpulated. The scripts were so funny, the personalities so endearing and the fan base so fervent that the National Broadcasting Company gave them contracts guaranteeing $100,000 annually. A feature film, “Check and Double Check,” included celebrity cameos by stars such as Duke Ellington and was a top box office hit until hurled down by “King Kong” in 1933. Freeman and Correll, however, were unhappy with the film. They appeared in blackface, and what had been implied in radio looked forced on the big screen.

So when television arrived on the scene, producers seized the opportunity to cast the show with Negro actors. “Amos will be played by Alvin Childress, veteran New York stage actor; Andy by Spencer Williams Jr.; and the Kingfish by Tim Moore,” read an announcement in February 1951.

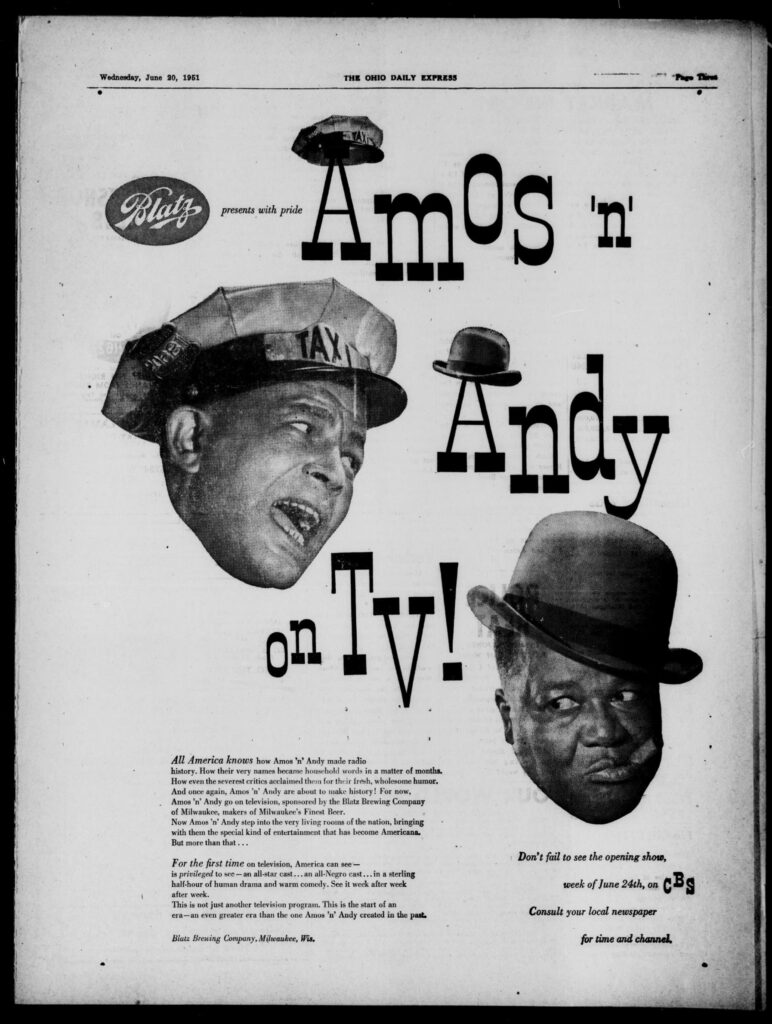

Blatz Brewing Company trumpeted its sponsorship. “For the first time on television, America can see—is privileged to see—an all-star cast…an all-Negro cast…in a sterling half-hour of human drama and warm comedy,” hails a 1951 full-page Blatz ad (italics in the original). “This is not just another television program. This is the start of an era—an even greater era than the one Amos ‘n’ Andy created in the past.”

That proclamation was prophetic, but not in the way Blatz intended. The first TV program aired on Thursday, June 28, 1951, at 9 p.m. EDT. What had previously been imagined now took shape—Amos in his bowtie and “Taxi” hat, Andy in his suit, bowler hat and ever-present cigar, talking in dialect and bumbling good-naturedly through misadventures in Harlem with Kingfish and other members of the Mystic Knights of the Sea Lodge.

Controversy erupted immediately. The show debuted during the NAACP’s annual convention in Atlanta. Publicity leading up to the gathering had scant mention of “Amos ‘n’ Andy” in either format; headlines centered more on starlet Josephine Baker’s cancellation because of strict segregation policies among hotels in the city. But attention quickly shifted when Dr. George D. Fleming of Texas presented an emergency resolution “condemning the derogatory manner in which Negroes are depicted on TV.” He contended that “such entertainment makes the uninformed and prejudiced believe that Negro is inferior.”

NAACP Secretary Walter White quickly fired off a telegram to Blatz officials asserting that the program was “a gross libel on the Negro and distortion of the truth.” Pull the show, he said. In addition, White wrote to the heads of roughly 100 national organizations asking them to join the fight and suggest that future scripts “be written so as to eliminate the present uniform presentation of the Negro in so unfavorable a fashion.”

The firestorm came as a surprise because the radio show had drawn few critics. The NAACP, however, came out blazing, listing 12 reasons for fighting the show.

“It tends to strengthen the conclusion among uninformed and prejudiced people that Negroes are inferior, lazy, dumb and dishonest,” it stated in an October 1951 Ohio Daily article. “Every character in this one and only TV show with an all-Negro cast is either a clown or a crook. … There is no other show on nationwide television that shows Negroes in a favorable light. Very few first-class Negro performers get on TV and then only as a one-time guest.”

The NAACP’s initial outburst of protest included “The Beulah Show,” a radio program begun in 1939. Similar to “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” it began with a white voice portraying a Negro, but in prime time it starred Hattie McDaniel, the Oscar-winning mammy of “Gone with the Wind.” McDaniel was signed to star as Beulah in the TV series, also set to air in 1951, but she fell ill, the debut was rescheduled and the role eventually went to Louise Beavers.

The upside of having Blacks on TV in any capacity spurred some pushback against the NAACP and support for the shows. A council of the Negro Actors Guild in New York City commended CBS “for its stand on the program because of what it termed the expressed willingness of CBS to increase Negro employment in this new medium.”

Blatz also stood by its sponsorship. “We certainly do not believe that there is anything derogatory to the Negro people in the Amos ‘n’ Andy show. It is our feeling that if there are legitimate objections they will be removed, but we do not believe the claims of the NAACP are well founded,” wrote Blatz president Frank Verbest in 1951.

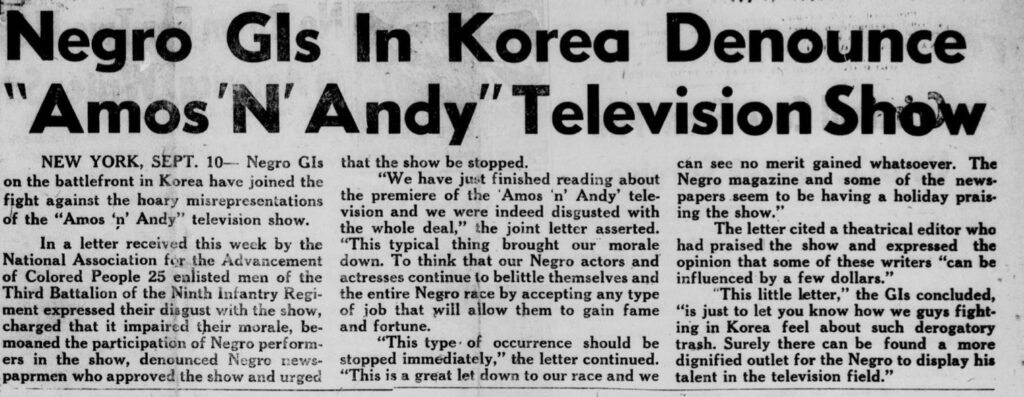

Controversy continued to spread, however. The local TV station in Milwaukee, Blatz’s hometown, discontinued the show. Even Black soldiers serving in Korea weighed in after reading about the show, writing that TV’s “Amos ‘n’ Andy” was “derogatory trash” and brought down their morale. “Surely there can be found a more dignified outlet for the Negro to display his talent in the television field,” the joint letter said, according to a front-page article in the Sept. 10, 1951, Ohio Daily Express.

Controversy continued to spread, however. The local TV station in Milwaukee, Blatz’s hometown, discontinued the show. Even Black soldiers serving in Korea weighed in after reading about the show, writing that TV’s “Amos ‘n’ Andy” was “derogatory trash” and brought down their morale. “Surely there can be found a more dignified outlet for the Negro to display his talent in the television field,” the joint letter said, according to a front-page article in the Sept. 10, 1951, Ohio Daily Express.

With continued protests and threatened picket lines in several cities, Blatz officials announced in March 1953 that the brewery would discontinue its advertising support. CBS-TV quickly followed by saying “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” despite good Nielsen ratings, would be discontinued after the 1953-54 season. Reruns were widely syndicated, however, and the radio program continued with Gosden and Correll at the microphone until 1960.

Blatz’s headaches weren’t over. Along with Pabst, Schlitz and three other Milwaukee breweries, it faced a strike in May 1953 by the 7,500-member CIO United Brewery Workers local chapter over hours and wages. The strike was short-lived, and Blatz proclaimed in ads that it was back as the No. 1 Milwaukee beer. However, Blatz had fallen from No. 3 in the nation in the early part of the century to No. 18 by the late 1950s. Pabst purchased Blatz from Schenley in 1958, but a protracted federal antitrust suit led to ultimate divestiture a decade later.

In an interesting twist of history, when the Blatz brand again became available in 1969, among the bidders was United Black Enterprises, a coalition of Black entrepreneurs who had put together $8 million toward the purchase. Though that offer fell short, one of its members, Theodore Mack Sr., went on to purchase Peoples Brewery in Oshkosh, Wis., which is widely regarded as among the first Black-owned breweries in the country. (The first Negro brewery in the U.S. was allegedly started in 1955 by a Black entrepreneur in Philadelphia, but that’s a story for another day.)

Protests against brewery hiring practices did not subside with the end of the “Amos ‘n’ Andy” show. Boycotts and strikes continued nationwide with increased success, using the argument that the money spent by Negroes on beer ($300 million nationwide in 1952) was not mirrored in jobs. “In the 440 breweries in the Land of the Spree, there are 82,534 employees of whom 63,668 are production workers. They draw down $292,000,000 in pay, much of which obviously comes from Negro consumers,” says a 1952 editorial. “But, my friends, less than 500 Negroes are employed by all of these breweries from coast to coast and from Canada to Mexico. Of this group…only 25 are production workers.”

One of numerous breakthroughs came in New York in 1953. Seven of the state’s breweries promised to give preferential consideration when hiring Blacks. “Immediately available are 100 jobs which previously were denied Negroes. They will pay $87 to $100 a week,” read a wire-service article.

Despite those and other advances, racial issues continue today. A recent survey by the Brewers Association, the trade group representing small and independent brewers nationwide, indicates that while Black people make up about 13 percent of the population, they constitute less than 1 percent of brewers (one source cites 60 black-owned breweries among more than 8,000 breweries in the country as of 2020). The BA in 2018 launched a diversity program, with Dr. J. Nikol Jackson-Beckham of Virginia as its ambassador, to address discrimination, hiring and harassment issues. Individual breweries also have offered grants and other incentives to promote equity.

And as far as “Amos ‘n’ Andy” goes, the nation’s fascination with—and mixed emotions about—the program certainly did not die in the 1950s. Syndicated reruns continued until 1966, when NAACP opposition again led to the plug being pulled.

In 1983, an hour-long documentary, “Amos ‘n’ Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy,” explored the background and development of the show, including interviews with the show’s actors as well as more current Black stars such as Redd Foxx of “Sanford and Son” and Marla Gibbs of “The Jeffersons.”

Foxx credited the show with providing a springboard for other black actors—plus it was funny. “I think it was a situation comedy that depicted Black people—some Black people—in an element. It was comedy, man, and it was laughs there, and that’s what it’s all about,” he said.

Gibbs added, “I don’t think it reflected the wrong image of Black people. I think it was the fact that it was the only image of Black people… Because that’s all we had, I think the NAACP was really trying to say we needed a balance.”

One final note: While the radio duo of Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll have their stars enshrined in Hollywood concrete, no such distinction goes to any of the actors in the TV show, despite its being the first all-Negro sitcom on television.

Blatz Beer is currently produced by the Miller Brewing Company under contract for Pabst Brewing Company. The documentary “Amos ‘n’ Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy” can be viewed on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Ka6u2WA_zU.