More than 80 years ago, Reuben Ray and Grady Jackson, both African-Americans, sat in a bar they co-owned in Detroit and wondered why whites, rather than those of their own race, were delivering beer to black businesses on their street.

“‘Grady, do you see what is happening here, man?’” recounts Reuben Ray II, Ray’s son, in the book Paradise Valley: Detroit. “‘The white boys are making money off us, delivering beer to our stores. Partner, I do believe we need to be in the beer business.’”

This ad by Paradise Valley Distributing Co. stakes its claim as “the world’s only colored beer distributors.” Taken from the Detroit Tribune of Saturday, March 23, 1940.

And so they gave birth in 1938 to the first black-owned beer distributorship in America—and in the world, according to their newspaper ads at the time. For years, the Paradise Valley Distributing Co. stood as a beacon of black enterprise—and success in the beer world—in what was called “the Harlem of Detroit.”

Their business in Paradise Valley stands out in the complex history of beer and race in America. Field slaves grew hops under the yoke of plantation owners, yet they also cultivated hops in their own gardens to sell for profit. Black women brewed beer in colonial kitchens, but always under the thumb of their mistresses. After Prohibition, national breweries hired blacks as sales representatives to increase business among minorities, but it took strikes and boycotts to open more sustainable union jobs on the production and delivery side of things.

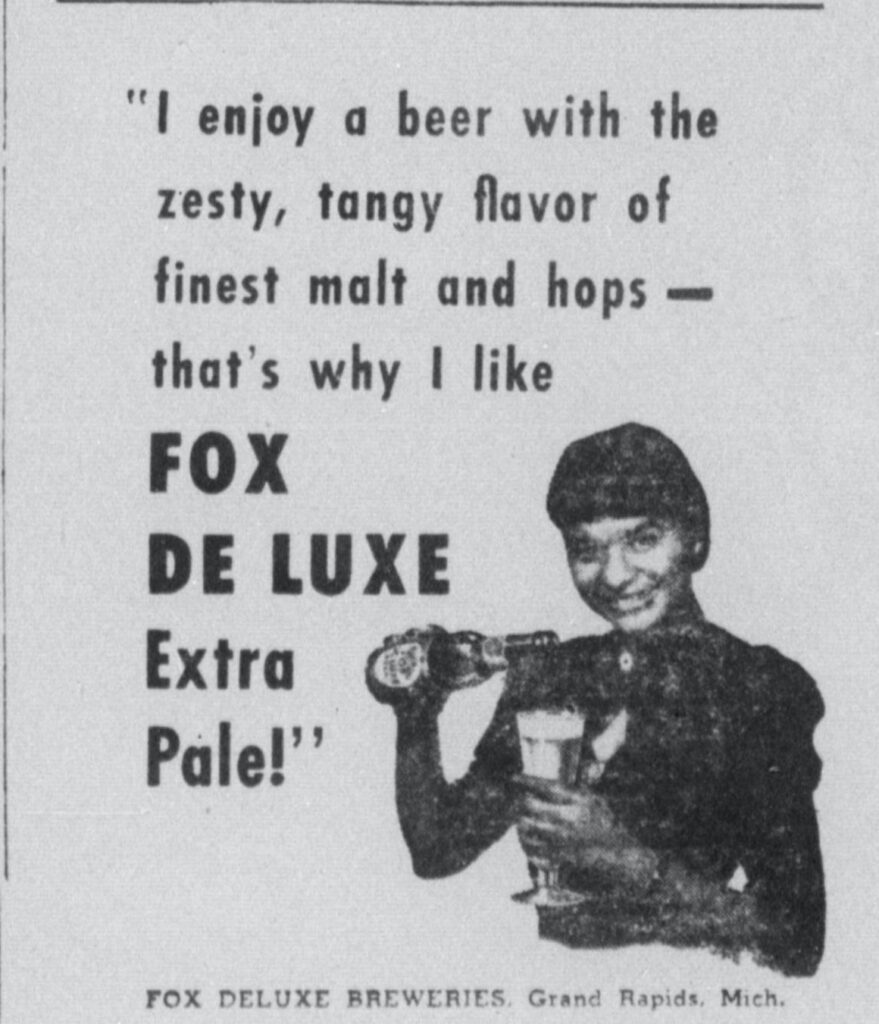

Fox De Luxe Beer ads, such as this one from 1946, regularly portrayed black men and women enjoying their products. Taken from the Detroit Tribune of Saturday, March 9, 1946.

Even now, the Brewers Association—the nation’s strongest representative of craft breweries—finds the racial component of the industry so tilted that it funds a diversity ambassador to address business practices. Dr. J. Nikol Jackson-Beckham, known as Dr. J among friends and students in her classes at Randolph College in Lynchburg, Va., is scheduled to be the keynote speaker at the Michigan Brewers Guild annual conference Jan. 8-10 in Kalamazoo. Dr. J. has established such prominence in the U.S. through her efforts that Imbibe magazine recently named her “Beer Person of the Year.”

Her appearance in Michigan seems well-timed after a tumultuous episode in the state’s craft beer sector last year. Founders Brewing Co. in Grand Rapids was involved in a lawsuit brought by a black employee who charged that racial discrimination existed in the workplace. The suit, which was settled in October, alleged that the state’s largest craft brewery tolerated a “racist internal corporate culture.” One of the claims was that the “N” word was used without repercussions. Testimony by one of the brewery officials was so evasive—he claimed he couldn’t confirm whether the employee or even Barack Obama was truly black—that a firestorm erupted on social media. Terms of the settlement were not disclosed, but Founders suffered bruises among many beer lovers and retailers.

Coincidentally, Grand Rapids also was the home of a production facility owned by Peter Fox Brewing Co. in the 1940s and ’50s. One of its flagship beers was Fox De Luxe, which enjoyed great popularity in the Midwest and beyond.

Black women as well as men were used in ads promoting Fox De Luxe beers from Grand Rapids, Mich. Taken from the Detroit Tribune of Saturday, June 21, 1947.

Fox De Luxe was featured in numerous ads showing black men and women enjoying beer. In our day and age, that doesn’t sound like a big deal. But in the 1940s, you were more likely to see blacks in stereotypical subservient settings, such as the Budweiser ads showing Negro train porters serving beer to whites. (To be fair, Anheuser-Busch hired and promoted blacks in sales and executive positions in mid-century.) Paradise Valley Distributing Co., however, set an earlier mark in history. The sense of excitement crackles in a Nov. 26, 1938, article in the Detroit Tribune describing the opening of the business under the headline “New Distributing Agency Opens Office.” “This time it is the real agency. A real honest-to-goodness beer distributing agency. Negro from the front office to the mop man. The new distributing agency will be … owned and operated by [Paradise Valley] people. Reuben Ray, who made Negro history during the past year as the only distributor of coin phonograph machines, will be president. And when you buy a bottle of [beer] … remember, you are really helping Negroes.”

That echoed earlier rallying cries. In a 1933 editorial in the Detroit Tribune, a black newspaper, Theodore R. Barnes wrote about the lack of jobs for Negroes among regional breweries and beer retailers despite President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the impending repeal of Prohibition.

Ray was a prominent figure in Paradise Valley, a black community similar to Jackson Ward in Richmond, Va., in its entrepreneurial vigor during Jim Crow days. In the 1930s, Ray found a profitable niche with his jukebox business; then he began lending money to other blacks to start their own businesses. The beer distribution venture started with one truck and a small shop on Beacon Street but soon relocated to larger quarters nearby. New partners joined and expansion continued with a fleet of “six street trucks and two highway truck units which hold 600-700 cases,” according to a Detroit Tribune article of Sept. 6, 1947. In 1941, the company had “22 employees of their racial group on their payroll with drivers of their trucks averaging from 60 to 80 dollars per week.”Initially, they represented beers from Koppitz-Melchers and other Detroit-area brewers. Early stalwarts in their portfolio (which also included wine and malt liquor) were Friar’s Ale and White Seal Beer, “the only beer obtainable in Detroit that is brewed with fancy malt.” Ads proclaimed, “Help Make Jobs for Colored Men and Get More for Your Money.”

“Suppose our cabarets, clubs, restaurants, and other businesses selling beer would demand that some Negroes be hired in these places. The men so hired would spend more money in these Negro businesses, thereby allowing them to do more business with the brewers. This matter should be considered.

“The Negro must awaken to the fact that sentiment means absolutely nothing to him, unless it is so constructed as to increase and enhance his economic status. To this day, with some people, the Negro is still ‘the forgotten man.’ He can expect nothing, only that which he through his own ingenuity and conquest can bring to pass in his favor. His courage as a fighter is legend. Let’s see it in action. The way is open; let’s take every advantage. They say a new deal—let’s see if they mean it.”

Those words still resonate, in Michigan and elsewhere. Dr. J’s topic is “Fans, Hands and Brands: Strategies and Tactics for Being Inclusive and Building Diversity in Craft Beer.” Given that Michigan lays claim to being “The Great Beer State,” with more than $2.4 billion in overall economic impact and 17,000 full-time jobs in its brewing industry, there seems ample opportunity to learn from history, in all of its complexity.

Pingback: 1930s beer ads teach lessons about Black lives that have mattered throughout history | leegraves.com

Yes! I am aware of Ben Henderson, another great figure in the story.