Note: I have long been fascinated by the tale of Peter and James Hemings, brothers and slaves of Thomas Jefferson. This was written as a precursor—a rough rough draft—of a possible screenplay, one I doubt will ever be fully fleshed. I envisioned it as a tale about food as well as people. Being as it’s Black History Month, I post this as an offering to the past that will feed the future. We tend to see slavery as a monolithic institution; it was, instead, a complex construct with many layers and nuances. Further, it was composed of individuals, and the more we know of their stories—of the people who were slaves—the better we can embrace our past and move toward a more compassionate future.

Peter and James

Our story begins in the suburbs of Paris. We see a wagon laden with fresh produce—carrots and lettuce and peppers and tomatoes–bouncing along the roads leading to the city and eventually finding its way to a bustling market. The scene bubbles with the sounds of vendors hawking their goods, everything from fresh beef to salted fish, and our humble farmer sets up his stand of produce amid this flurry of activity. Our eye focuses on a young black man dressed in the finest French fashion, strolling through the market with two servants at his side. He leans over to smell and feel various items, carefully judging their quality, instructing the servants to purchase this and that, and soon several baskets are packed with meat, vegetables, spices and more.

Cut to a scene that evening. We see a kitchen with steaming pots and sizzling pans, dozens of white cooks chattering in French while tending to dishes in various states of preparation. Moving quickly from station to station is our young black man, tasting a soup, sampling a wine, supervising preparations in fluent French. He is the master of the scene. Our eye follows one of the servants bringing an elegantly prepared terrine into a large dining room where an animated assemblage of aristocrats dines, their conversation peppered with graceful gestures, clever witticisms and understated passion. At the head of the table sits a thin, red-haired man whose dress is conspicuously less elaborate than that of his guests. He smiles bemusedly at the exchanges whirling around him; when he speaks, his words cut through the thicket like a rapier—all are eager to hear his thoughts, and he is equally eager to be heard, appreciated and liked. As the terrine is served, Jefferson’s smile broadens; it is delicious, a tribute to the mastery of his chef and earns the nods and whispered compliments of his guests.

The man at the head of the table is Thomas Jefferson. The man at the market and in the kitchen is James Hemings. Before arriving in Paris in August 1784 with Jefferson, as the latter assumed his role of Minister to France, Hemings was a slave in Virginia, one of numerous siblings who constituted one of history’s most storied slave families. James Hemings had been a near-constant companion of Jefferson’s throughout his travels preceding and during the Revolution. Now Hemings was in Paris for the specific purpose of learning French cuisine. Jefferson not only paid for Hemings’ lessons at the finest French cooking schools, where he rubbed shoulders with the most privileged of French society, but Hemings also was paid a salary, took lessons in the French language and had nearly total freedom to explore Paris when his duties and convenience allowed. If he wished, Hemings could at any moment petition for his freedom, which would have been speedily granted. It was illegal for French citizens to own slaves, and any visitor who brought slaves to the country was required to register them. Jefferson, however, never registered Hemings (or Sally Hemings, who would arrive on a later ship with Jefferson’s youngest daughter), so for all intents and purposes, Hemings was a free man in France. We see in our mind’s eye his sessions at the culinary schools, his exploration of taverns and inns in Paris, his flirting with fawning ladies smitten by this dashing, cultured black man.

Now the camera cuts from the Parisians dining with Jefferson to a mountain estate in Virginia where a ragged, hunched slave pushes a small cart bearing produce to the rear of Monticello. Martha Jefferson, Thomas’ daughter, appears in everyday clothes befitting a plantation mistress, and she picks among the items, finally emptying much of the cart and handing a handful of coins to the hunched slave. He departs, taking the vegetables to a small shanty, and our scene follows in a parallel of the French episode, only here there is but a single pot over a fire that warms the entire earthen-floor cottage. Stew fills wooden bowls as a family of slaves gathers around a rough-hewn table. They pray; they dip crusts of bread into the stew; they talk quietly in a vernacular as foreign to outsiders as any French; they eat with an urgency driven by gnawing hunger; they laugh as well at each other’s stories, and the meal ends with smiles and thanksgiving. One of the men retires to a chair by the fire, picks up a needle and thread, and stitches a seam in a pair of trousers. This is Peter Hemings, brother of James Hemings, and tailoring is his talent. Much of Jefferson’s clothing worn on the voyage to France came from Peter’s hands (though Jefferson quickly realized he needed to upgrade his wardrobe to hobnob with the French elite).

Now let us cut to a less cinematic and more straightforward telling of our story. James and Peter—along with Sally and other siblings—were members of a family sired by the father of Jefferson’s wife, Martha, who had died in 1782. The Hemingses were thus related to Jefferson’s wife and enjoyed special status in the enslaved community at Monticello. They saw to household chores rather than working in fields or in the nail factory that provided income to the estate. There are few physical descriptions of the Hemingses other than that they were light-skinned; Sally, renowned for her role in Jefferson’s life, was described as being very attractive. She was 14 when she was tagged to accompany Polly Jefferson to France. Abigail Adams remarked on Sally’s youth and how ill-prepared she seemed for her responsibilities, so a question looms about why Sally was chosen for the trip.

A larger question arises about why James and Sally did not stay in France, where they would have been free. James could certainly have earned a living as a chef, probably enough to support Sally as well. Why return to Virginia? Sally might not have realized the nuances of her possibilities, but James, being out and about and circulating in French society, would certainly have known his options and communicated them to Sally. Our camera would depict his learning, his telling to Sally and their discussions. Our source for much of this comes from The Hemingses of Monticello, required reading along with the books of Cinder Stanton (my one-time neighbor) about the enslaved people at Monticello.

One factor in the tale is the role of family. Slaves in general had strong family ties, perhaps partially because of the threat that at any moment a family member could be sold, never to be seen again. The Hemingses were tight; remember that they had been inherited by Martha as a group, and they were allowed to remain as a family at Monticello. Another factor is that, despite its appeal, France was a foreign land, particularly to Sally. One can imagine her feeling of alienation in a culture she didn’t understand, in a society experiencing extreme volatility. Still, she and James plotted to stay. The fact that each of them struck a deal with Jefferson indicates they were aware of the leverage they had in the situation. Jefferson’s bargain with James was that he would be granted his freedom in Virginia as soon as he trained someone to be an equally competent chef. With Sally, who initially refused to return to Virginia (she was pregnant with Jefferson’s child), he promised that all her children would have their freedom upon turning 21.

Let’s insert some spice. There are suggestions that James developed a romantic relationship while in Paris. We should insert this into the story, for reasons explained in a bit. Also, Jefferson had an affair of the heart (and possibly other parts of anatomy) with Maria Cosway. Though she would never say so to Jefferson, this might be a thorny topic with Sally and James, and we can imagine conversations about the dual standard of Jefferson bedding Sally and romancing Cosway. Not that Jefferson owed Sally any romantic allegiance, but it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that having a taste of freedom in France would have fed Sally’s desire to be treated as a human being rather than a slave.

We return to Virginia. Sally is great with child, but our camera focuses largely on James and his tutelage of Peter in French cuisine. James is known to be a borderline alcoholic (if not full-fledged) and have a hot temper (his rages were noted in records); both these, plus his impatience to earn his freedom, would be part of our story here. Peter, whose intelligence is often remarked upon by Jefferson, is a quick study and soon is able to handle the culinary responsibilities at Monticello. Keep in mind that Jefferson entertained often, was a gourmand of great distinction (a foodie of the first order) and demanding in his expectations. His guests spanned the spectrum, from plantation neighbors to the fledgling nation’s most powerful and sophisticated figures. We can assume Peter Hemings developed a sophisticated appreciation for food, its presentation and its importance in the Jefferson household. After all, he must learn the nuances of preparing macaroni and cheese and crème brûlée—novelties James brought to this country from France (though that has been disputed by some historians).

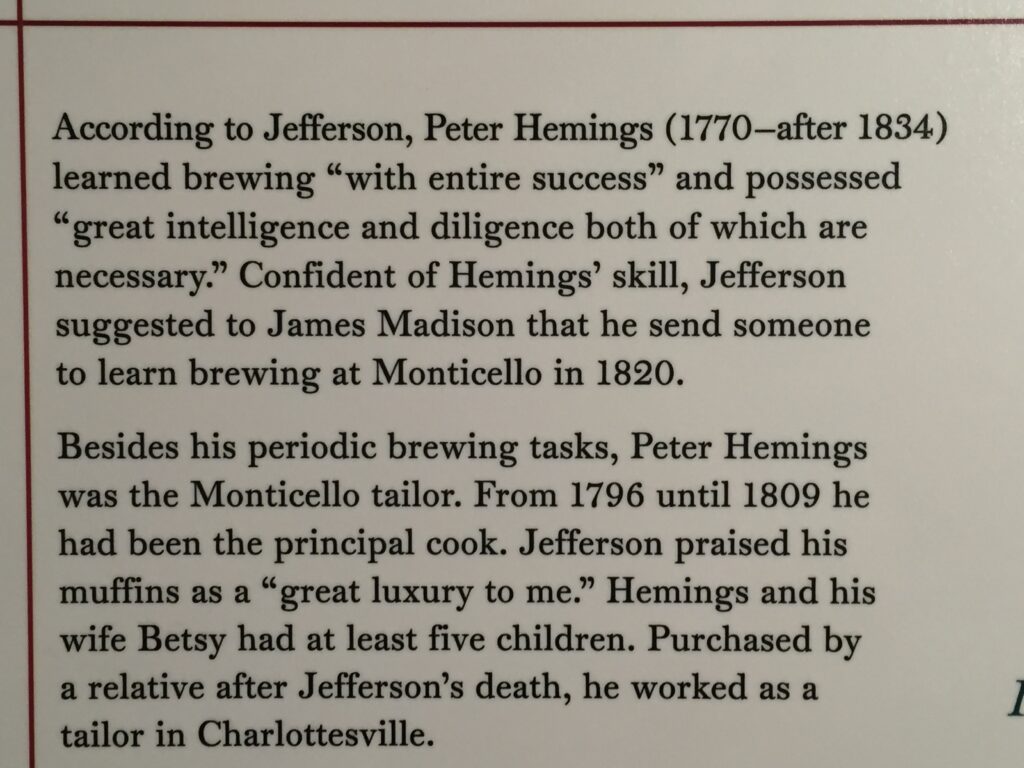

A display at Monticello pays homage to Peter Hemings’ skill as a brewer. He was trained by Capt. Joseph Miller, who had worked professionally as a brewer in London. Photos by Lee Graves

So, 11 days after returning to Monticello in 1794, James begins training Peter, his younger brother. He also travels with Jefferson to New York and Philadelphia; the relationship with Jefferson is complex—Hemings arguably knows him better than any person, having traveled with him, served as his personal valet, prepared his meals and been by his side during intense times. In February 1796, James achieves true freedom, despite Jefferson’s efforts to sweeten his attachment and loyalty through gifts and privileges. James departs for Philadelphia, then begins a restless period of travels at home and abroad. His return to France opens the door to suggestions of the romantic connection mentioned (conjectured) earlier; spice for the pot. James’ behavior and actions indicate his continued attachment to Jefferson a nd expectations that the master of Monticello will hire him back into service. Those expectations ratchet up when Jefferson becomes president in 1801. Meanwhile, we see Peter settling into his chores as chef and tailor. We dwell on the foodie part here on three levels—what was served at Monticello, what the Hemings family ate, and what was consumed by other slaves in their meals. There must have been an interesting dynamic for Peter, what he prepared, what he ate, and what others of less privilege ate.

nd expectations that the master of Monticello will hire him back into service. Those expectations ratchet up when Jefferson becomes president in 1801. Meanwhile, we see Peter settling into his chores as chef and tailor. We dwell on the foodie part here on three levels—what was served at Monticello, what the Hemings family ate, and what was consumed by other slaves in their meals. There must have been an interesting dynamic for Peter, what he prepared, what he ate, and what others of less privilege ate.

Our tale reaches a climax after Jefferson’s election. James Hemings has every expectation of being requested to fill the role of White House chef. He has traveled far but never left the pull of Jefferson’s personality. He indicates several times he is eager to work for Jefferson again, as a paid free man. James has settled in Baltimore; Jefferson knows he is there and five days after his election writes to the innkeeper where James is staying. “Could I get the favor of you to send for him & to tell him I shall be glad to receive him as soon as he can come to me,” Jefferson writes. The innkeeper responds that his message has been relayed but that Hemings said “he would not go until you should write to himself.” It seems Hemings is offended at Jefferson sending for him, summoning him like a slave rather than contacting him directly. “He was an adult free man now,” a historian writes. “He could read and write. He knew that Jefferson spent hours at his desk writing to anyone under the sun. Why not a line formally asking him to come to Washington? Being the president’s chef de cuisine was a serious job. Why not spell out in writing all that was expected?” The interchange turns into a matter of egos, both men feeling the sting of being slighted. Jefferson, after all, had just been elected President of the United States. Who was this man, a former slave he had known since boyhood, to be so demanding? Hemings also wants respect, especially from the man he had served in the most intimate of situations. Neither person communicates directly with each other at this point. The complexities of their relationship speak volumes—matters of loyalty, mutual affection, self-respect, newfound freedom in a former slave, newfound stature in the country’s most powerful man. Jefferson quickly turns elsewhere, on the surface because he needs to fill the chef’s position speedily. He hires Honore Julien, former chef for George Washington. Oddly, here again the whole transaction of procuring Julien is carried out through a third party.

We can assume this constitutes a serious blow, bruising if not crushing, for James, whose ego borders on the prima donna. He returns to Monticello briefly to work as a paid chef and to enjoy the company of family. But working as a free man in the plantation setting proves more than he can handle, and in September 1801 he leaves Monticello. It is the last time any of his family see him alive.

Within a matter of weeks, Jefferson receives word at the White House that Hemings has killed himself. “The news appeared to have stunned Jefferson, and he wrote for confirmation.” The same innkeeper, William Evans, writes back that Hemings had, in fact, “committed an act of suicide.” Hemings had been “delirious for some days previous to his having committed the act, and it is as the General opinion that drinking too freely was the cause.” It was, Jefferson wrote, “a tragical end.” Indeed. Hemings, trained in the most sophisticated of culinary arts, had ended working at the equivalent of a greasy spoon, having been passed over and disrespected. His final days, we can assume, were spent in a drunken spiral, his spirit torn by conflicting currents—a free man who would never be treated as an equal human being, whose family still lived in slavery.

No records document the reaction of Peter to news of James’ death. We know they were close—Peter named one of his sons after James. But the camera shows us a different personality in Peter, one never tantalized by the prospect of freedom, perhaps a soul more resigned to his plight, aware of his privilege within the Monticello community and glad to have special skills and knowledge. A fascinating interplay of scenes would be glimpses of James’ downhill slide into alcoholism and Peter’s training by a professional brewer from London. Peter was, after all, the first African-American to be so trained, adding to his value as a tailor and chef.

We fast forward to the end of days. Jefferson dies on July 4, 1826. His estate is deeply in debt. An auction is held the following January, and it will have immense impact on Monticello’s slave community. Attending the auction is a man named Daniel Farley, a free black man living in Charlottesville whose reputation suggests something of a lovable rogue—gambler frequently in trouble with the law, a talented fiddler, a ready host for rowdy friends. Records suggest he was Peter Hemings’ nephew. Hemings is 57 at the time of the auction; his value is appraised at $100, a respectable sum for an aging man thanks to his many skills. Farley made a single purchase that January day—for one dollar, he bought “Peter. Old Man.” As one historian notes, “The token sale price suggests that the wish for his family members to purchase his freedom was recognized by those present at the sale.” Peter Hemings lived out his days as a tailor in Charlottesville, sharing a house with Sally and, we assume, fixing their meals. Our tale ends with scenes of quiet resolution, particularly in contrast to James’ end. However, many questions will never be resolved, and the peace of the final chapter does not untie the Gordian knot of complexities regarding freedom, slavery, self-dignity, family, loyalty, affection, power and privilege.

As a coda, these words from Annette Gordon-Reed: “James Hemings’ was a singular life: an eighteenth-century Afro-Virginian who lived abroad in France, who was passionate and intellectually curious enough to hire a tutor to teach him to speak and think in a different language, who was literate, who became a chef de cuisine, who negotiated his freedom, and who continued to journey far and wide after he became a free man. Surely it broke his family’s heart to lose him.”