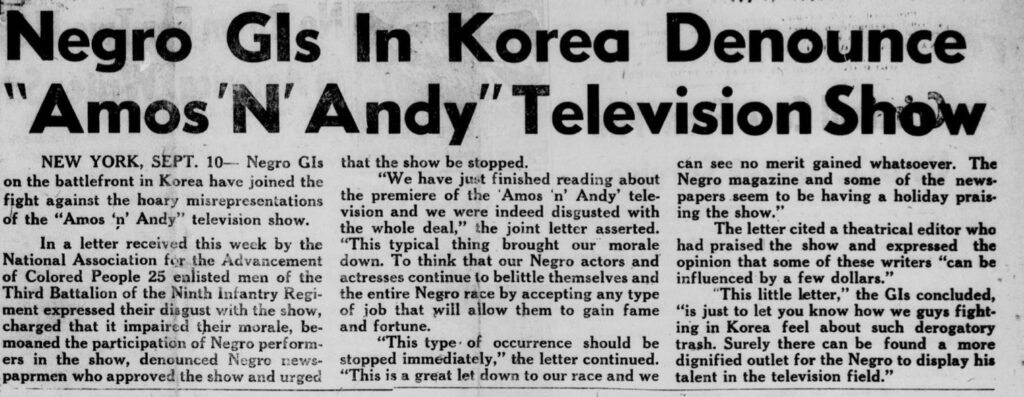

When Ardent Craft Ales in Richmond, Va., used a recipe from a 1700s cookbook to make a batch of persimmon beer in 2014, the effort made international headlines.

“A drink brought back from the grave!” trumpeted the Daily Mail in England.

The excitement was palpable when aficionados gathered at Ardent to toast the first public pouring of the light, effervescent brew.

“You can feel a connection across time when you’re drinking something that maybe hasn’t been drunk for a couple hundred years,” said Paul Levengood, then president of what is now the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, sponsor of several “History on Tap” programs. “It’s a fun way to bring the past into the present.”

That past has a richer context than many realized when they drank Ardent’s version of “Jane’s Percimon Beer.” The history of persimmons and persimmon beer in early America represents a unique intersection of three cultures—English settlers, Native Americans and enslaved West Africans—and a beverage that became iconic in the Old South.

“This beer when properly made, in a warm room, is an exquisitely delightful beverage as the writer knows from personal trial and experience,” wrote a South Carolina journalist in the Anderson Intelligencer in 1876. “[It] is to the connoisseur of temperate taste, not inferior to the fermented juice of the grape.”

During persimmon beer’s heyday, newspapers from New York to New Orleans carried recipes, including ones credited to Thomas Jefferson. Virginians can claim particular connection to the fruit and the beer. The scientific name, ascribed by Carolus Linnaeus in 1753, is Diospyros virginiana. The fruit’s common name is derived from Native Americans; Powhatans called it “putchamin;” others, “pessamin” or “pasiminian.” One scientist writing in 1896 said the Native American name translates to “choke fruit”—biting into a persimmon before it ripens in the fall will turn your mouth inside out.

Persimmons were a staple among the Powhatan, Cherokee, Rappahannock and others, “so valued for their fruit that sometimes the Native people would build their homes near the trees,” says a Virginia Foundation for the Humanities publication. The fickle fruit was eaten raw or dried for use in a variety of foodstuffs, including bread that was shared with English settlers during Jamestown’s infancy.

To those Old World newcomers, the persimmon was a novelty; persimmons are not native to Europe. The first description is credited to an anonymous author writing in 1557 about Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto’s expedition in the North American Southeast. Englishman Thomas Hariot penned an account in 1587, and Capt. John Smith followed with this: “Putchamins grow as high as a Palmeta; the fruit is like a Medler; it is first greene, then yellow, and red when it is ripe; if it be not ripe, it will draw a man’s mouth awry, with much torment, but when it is ripe, it is as delicious as an Apricot.”

The story takes a fascinating twist with the arrival of enslaved West Africans in Virginia in 1619. Thanks to recent research by Michael W. Twitty, author of “The Cooking Gene,” and others, we can envision a light bulb moment when these slaves encountered their first persimmons. Diospyros virginiana would have reminded them of their own Diospyros mespiliformis, the African persimmon from what is commonly called the jackalberry tree. Its fruit, known as “alom” to the Wolof and “kuku” to the Fula peoples, was used for medicinal purposes, as a food source used in bread and—wait for it—to make beer.

“Europeans and Africans might ultimately have been the ones who brought the fermentation of Native American fruits into Southern culture,” Twitty writes. “Given some of the connections between indigenous foods and those found across the Atlantic, it might be more in the lap of West Africans that we owe the existence of beers made from persimmons mixed with honey locust. In any case, it’s clear two ancient strategies emerged.”

What about the Powhatans, though? If persimmons were so important to their tribe and others—Rappahannock, Cherokee, Algonquin—wouldn’t they have been brewing persimmon beer?

The consensus among historians is that alcoholic beverages were not a part of Native American culture in the Southeast before the arrival of Old World settlers (tribes in the American Southwest, however, were known to make a fermented drink called tiswin from corn).

Two of our earliest sources—William Strachey and Capt. John Smith—state that natives they encountered drank only water. Noted author Helen Rountree told me there’s nothing in the old records about the use of persimmons in making any kind of drink. She added that there are only two clear documentary references to Powhatan drinking before the late 17th century. A 1983 paper also concludes that while there is some oral tradition for its 19th century use, “several early sources from the area deny any aboriginal intoxicant there.”

That said, there are references indicating that persimmon beer caught on among indigenous folks at some point. A publication by Washington College in Maryland states: “The fruits of Diospyros virginiana were used by the Cherokee, Comanche, Rappahannock and Seminole for food and beverages. The Rappahannock rolled fruits in corn meal, brewed in water, drained, baked, and mixed with hot water to make a beer.” Dr. Julie Markin, associate professor of anthropology at Washington College, said, “A ‘beer’ in this instance is likely to be of the root or ginger beer variety and not an alcoholic beverage.”

A 1925 monograph by Frank G. Speck titled “The Rappahannock Indians of Virginia” describes the home of an elderly Rappahannock named Bob Nelson as “typical” of the time, with several acres of cornfields surrounding log houses for Nelson and his family. “In Bob’s house the visitor will not look in vain for the old-fashioned home-brewed persimmon beer.”

And numerous newspapers in the 1800s carried this one-sentence “filler:” “Persimmon beer was the favorite drink of the North American Indians.” Without attribution, it has little historical credibility, but it certainly stirs both our curiosity and imagination. Regardless, it certainly refers to the period after European contact.

It’s not hard to envision circumstances when that first batch of persimmon beer might have been brewed. Slaves, Native Americans and indentured servants rubbed shoulders often in work settings, and a bit of Powhatan persimmon bread or cake could easily have been appropriated for brewing along with corn or honey locust pods (frequently mentioned in colonial recipes). The first mention of persimmon beer in English by Robert Beverley in 1705 describes using dried cakes of the fruit for brewing. Beverley also ascribes persimmon beer—along with beer made from molasses, potatoes, “Indian corn” and just about any other source of fermentable sugars—as being made “among the poorer sort,” i.e. indentured servants, slaves and Native Americans.

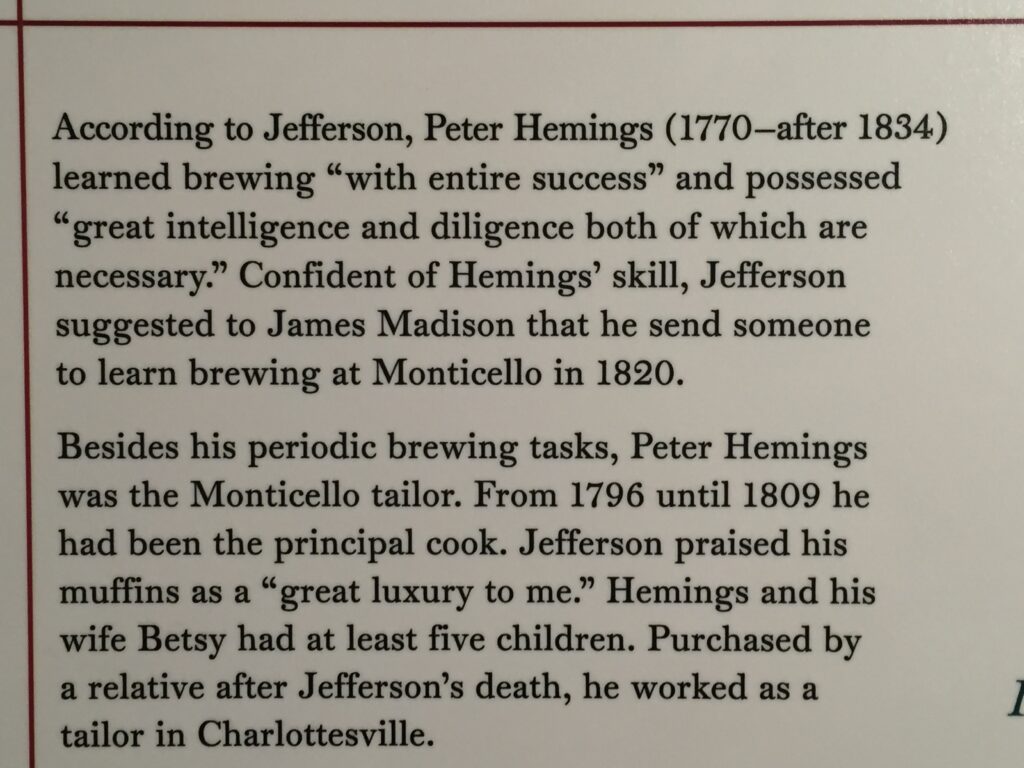

Actually, persimmons and persimmon beer quickly developed an esteemed position among the gentry as well as within enslaved communities. One of George Washington’s estate managers, his cousin Lund Washington, in 1778 wrote, “I find from experience there is a fine spirit to be made from persimmons, but neglected to gather the item for that purpose; only got some for the purpose of making beer.”

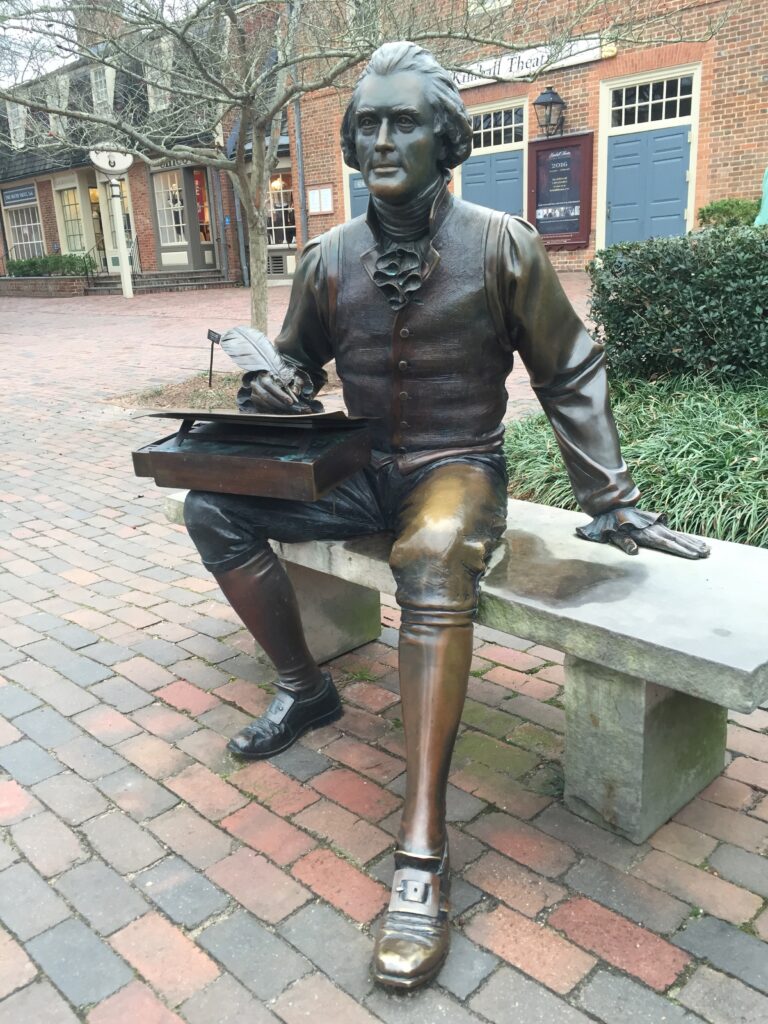

Thomas Jefferson was notoriously cagey about beer recipes, saying he had none and “I much doubt if the operations of malting & brewing could be successfully performed from a [recipe].” Yet in 1805 he responded in detail to a request for persimmon beer (see sidebar).

The drink was more than a nicety among African Americans. “That old persimmon beer was half of our living,” said an elderly Nick Waller when interviewed for the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s. “Us chillun would gather persimmons by the bucketfulls. Mother would cook ’em with wheat bran and make it out into the big pones that she used to make the beer mash and she put lots of [honey] locusts in it. That beer was really good and so refreshin’ after a hard day’s work.”

It was a special treat at Christmas. “Apple cider and ’simmon beer,/ Christmas comes but once a year” was a popular couplet.

Persimmon beer technically was more a cider than a beer, given that the fruit is actually a berry. Both the American and African persimmons are ebony trees, and the hard wood proved ideal for everything from furniture to firewood—it was even used for golf club heads. Confederate soldiers used persimmon seeds for buttons and ground them to make coffee during the Civil War. Both African and American ebonies were prized for their medicinal value and used to treat diarrhea, dysentery, diphtheria, hemorrhoids and sexually transmitted diseases.

“Shavings of the [jackalberry] wood, combined with the pods of Acacia nilotica and roots of Borassus, are pounded in water and boiled for about two hours, after which the liquid is used in Nigeria to rinse the mouth for treating toothache,” says a Plants for a Future publication.

The jackalberry range extends through a score of African countries, including Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Angola, Benin and others that were central to the transatlantic slave trade. A 2013 article calls Diospyros mespiliformis “the best fruit in Africa.” After all, diospyros translates to “fruit of the gods.”

Beer made from the jackalberry fruit was but a small part of a rich brewing tradition in western Africa. From the origins of mankind in southeastern Africa, nomadic tribes migrated northeast to the savannah that was rich with wild grains. While barley was prized as the soul of beer in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, millet and sorghum filled African clay brewing pots. (That tradition has continued among peoples such as the Kofyar in Nigeria, who “make, drink, talk and think about beer. It is a focus of cultural concern and activity,” according to a 1964 anthropological study.)

The African slaves who arrived in the New World were forced into an alien brewing culture—growing hops in the fields (and in their own gardens for sale to plantation owners), brewing ale from barley, corn, wheat, molasses, potatoes, even pea pods in plantation kitchens. So it’s little surprise that persimmons—a balm for homesickness as well as an ingredient for fermented beverages—were embraced and became a matter of communal identity.

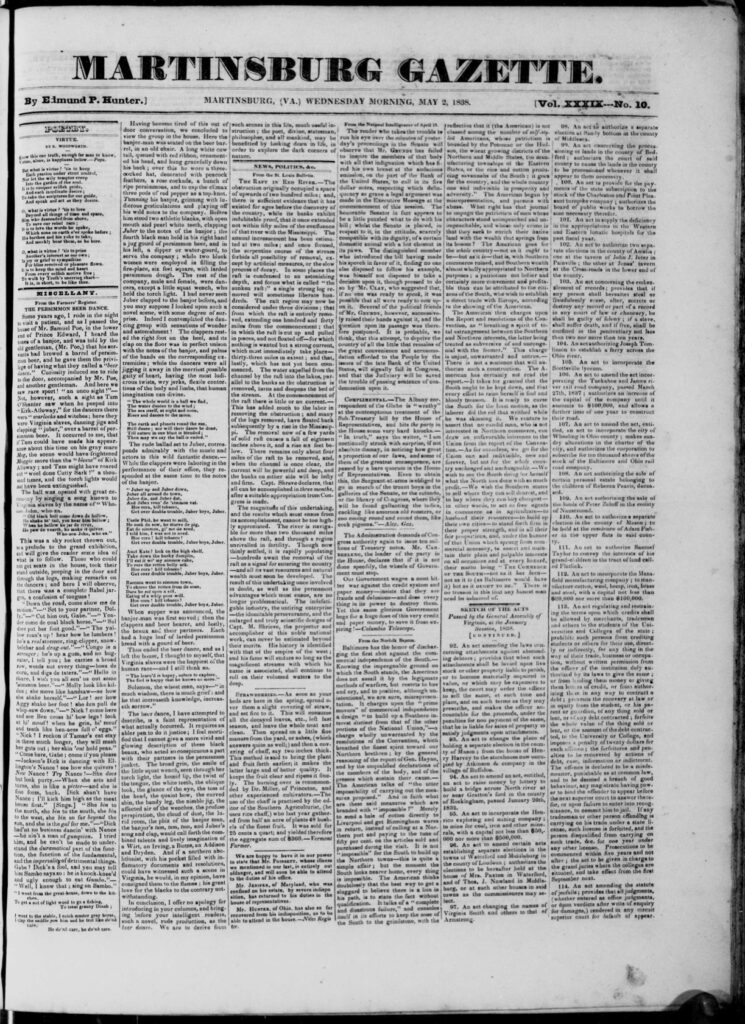

1838 Persimmon beer dance amazing

A long article from the Farmers’ Register published in an 1838 edition of the Martinsburg Gazette in Virginia gives an insight into that communal importance. Under the headline “The Persimmon Beer Dance,” the story describes “Virginia slaves dancing jigs and clapping ‘juber,’ over a barrel of persimmon beer.” Dancers moved “in perfect unison” to a plunking banjo as a “black man held in his right hand a jug gourd of persimmon beer, and in his left, a dipper or water gourd to serve the company; while two black women were employed in filling the fireplace, six feet square, with larded persimmon dough.”

A different but equally vital identity existed on the other side of the racial divide. Essayist George Bagby, writing in 1866, declared that persimmon beer was among the food items needed to be a “true Virginian” (his list also included eating squirrel, “old hare” and “snappin’-turtle eggs,” so we won’t go there).

A 1915 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture declared, “The only fruit that equals the persimmon in food value is the date.” A 1912 article in The Progressive Farmer and Southern Farm Gazette stated, “It has been said that the blackberry is the king of wild fruits of the South. If it be true, we can safely add that the persimmon is next to the throne.”

Thomas Jefferson and others said their recipes yielded a “very strong” beer. Yet when Georgia teetotalers rallied in support of Prohibition in 1885, “Persimmon beer and ginger cakes were served in abundance.” They claimed it had no alcohol.

The U.S. Supreme Court concluded otherwise. In a case decided in 1887, “The Supreme Court of the United States has decided that persimmon beer, blackberry cordial and currant wine are intoxicants, and that the inherent right of a citizen does not grant him the privilege of putting persimmons into a receptacle and fermenting them for his own use, if the State in which he lives decides the contrary,” according to an article in West Virginia’s Wheeling Daily Register. The case grew out of a Kansas Prohibition law “because its Legislature does not think persimmon beer good for [people]. The next thing will probably be to arrest every child caught shaking a bottle of ‘licorice water.’”

Jefferson and Washington weren’t the only chief executives with a taste for persimmon beer. President-elect William Howard Taft accepted an invitation to speak in Atlanta in January 1909, and the politician made a point of requesting a particularly Southern dish—possum and “sweet taters.” Persimmon beer, long associated with that delicacy, was selected as a necessary accompaniment, and preparations had many biting their fingernails.

“All Georgia is anxiously watching the daily bulletins from the barrel of persimmon beer that is being brewed for the ’possum supper to Mr. Taft next week,” read one local newspaper account. “It is already in the process of fermentation, under the prayerful guardianship of the committee on entertainment, and no true Georgian will breathe easy until it is announced that the beer is ‘right.’ The reputation of the state is at stake on this barrel, as, any Georgia farmer will say, you never can tell about a keg of persimmon beer until it is ready to tap.”

The Georgians’ reputation proved secure. The banquet featured 100 gallons of the beer, 100 possums (the largest weighing 24 pounds), champagne and great cheer among the 500-plus attendees. Taft, who did not carry the state in his presidential campaign, raised a toast with a glass of “good old ‘simmon’ beer: ‘I may not have been successful in winning the South, but the South has already won me,’” he said.

Not everyone thought as highly of persimmon beer, however, as the Georgians and their guest. The Omaha Daily Bee scowled: “Persimmon beer was served at some of the banquets tendered to Mr. Taft in Georgia. The only good thing about persimmon beer is that it makes a man regret having ever drunk anything but water.”

While that opinion might seem harsh, the American persimmon was waning in popularity and prevalence by the new century. Among beer drinkers, lager became the national darling. Many African Americans moved off plantations and out of the tree’s natural range. A 2005 scientific treatise adds another factor: “Common persimmons never caught on as a horticultural crop and were eclipsed at the end of the 19th century by the recently introduced larger fruited Japanese persimmon or kaki (Diospyros kaki).”

The decline was roundly lamented by old-timers. “We wish to say that in truth time brings back no joys like those it takes away. It has not brought us a glass of persimmon beer for sixty years, and we are grown as thirsty for it as old RIP VAN WINKLE could have grown for any Dutch beverage,” claimed an 1878 Richmond Dispatch writer with obvious tears in his beer.

Though persimmons and persimmon beer have lost their prominence, they are still celebrated in various ways. The town of Mitchell, Ind., has held a Persimmon Festival since 1947. And Ardent Craft Ales isn’t the only craft brewery to bring persimmon beer “back from the grave.” Fullsteam Brewery in North Carolina has produced a seasonal, First Frost, using foraged persimmons. In addition, noted brewer and historian Travis Rupp of Avery Brewing Co. in Colorado researched Thomas Jefferson’s brewing to produce Monticello Ale in 2020, the 10th of his Ales of Antiquity series. The beer incorporated persimmon, malted wheat, bran, English hops and English yeast. It was fermented in oak and cellared before its release.

“Without a doubt, this persimmon wheat ale is extremely unique and the most bizarre of the turn of the 19th-century beers I’ve produced in the last 12 months,” Rupp wrote.

“Sali” is the Cherokee word for persimmon, used in this sour ale brewed by 7Clans brewery in Asheville, N.C. Photo courtesy of 7Clans BC.

The brew has come full circle with Morgan Crisp and 7Clans brewing in Asheville, N.C. A native Cherokee, Morgan told me about memories of her father and grandfather eating freshly ripened persimmons, and that was one inspiration for the brewery to develop its Sali Persimmon Sour (Sali means “persimmon” in Cherokee). The fruit’s pucker factor inspired them to choose a sour ale, she said, which uses Liberty hops, persimmon extract and kettle souring with lactobacillus. “We’re choosing ingredients that are not typically used now. A lot of the traditional foodways were lost,” she said. “It’s been very personal with me.

“My story is told through my beers—as a woman, as a mother, as a Cherokee tribal member,” she added in a magazine interview. “I want to pass on all that I have learned.”

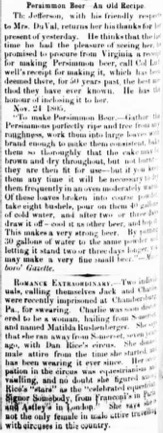

Thomas Jefferson’s Persimmon Beer

The following is based on an 1805 letter from Jefferson to a Mrs. Duval. He credits the recipe to a Col. Ludwell—presumably Col. Philip Ludwell III—and notes the recipe “has been deemed there, for 50 years past, the best method they have ever known.” At least one other recipe has been attributed to Thomas Jefferson.

To Make Persimmon Beer.—Gather the Persimmons perfectly ripe and free from any roughness, work them into large loaves with brand [sic] enough to make them consistent, bake them so thoroughly that the cake may be brown and dry throughout, but not burnt—they are then fit for use—but if you keep them any time it will be necessary to dry them frequently in an oven moderately warm. Of these loaves broken into coarse powder, take eight bushels, pour on them 40 gallons of cold water, and after 2 or 3 days draw it off, cool it as other beer, and hop it. This makes a very strong beer. By putting 30 gallons of water to the same powder and letting it stand 2 or 3 days longer you may make a very fine small beer.

Millie Evans’ Persimmon Beer

Millie Evans was a black woman from Arkansas who was interviewed in 1936 as part of the Federal Writers’ Project, a Depression-era effort to record the narratives of African Americans born into slavery.

“Gather your persimmons, wash and put in a keg, cover well with water and add about two cups of meal to it and let sour about three days. That makes a nice drink. Boil persimmons just as you do prunes now day and they will answer for the same purpose.”